Microchip: A Case Study of Oregon’s Public-Private Partnerships for Economic Development

16 Feb 2024

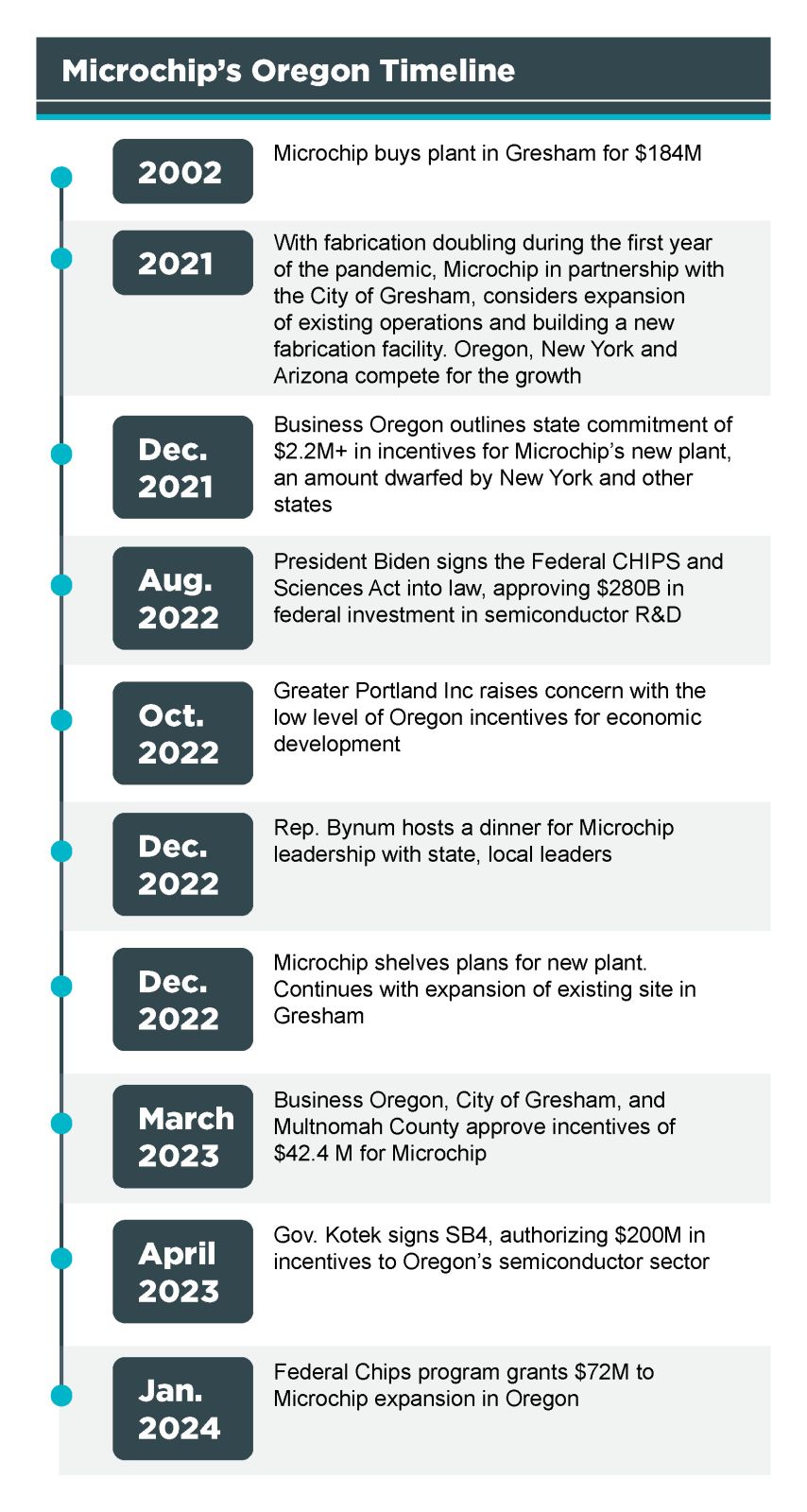

When the U.S. Department of Commerce announced in January the first federal chips program dollars would go to Microchip’s semiconductor fab in Gresham it was a symbol of strength for the Silicon Forest.

Home to one in seven U.S. semiconductor jobs against a backdrop of a national priority to increase domestic chips production, Oregon reaffirmed its leadership in the sector.

(For a PDF version of this case study, click here.)

And Microchip, expected to receive $72 million from the federal chips program, is now proof positive of what can happen when government works with business to help spur economic development

But it didn’t necessarily start that way. In Oregon, government support to attract and retain businesses, like Microchip, has been soft to say the least, until now.

New Demand, Old Paradigms

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare Oregon’s and America’s tech challenge. Research and development could only take U.S. companies so far when manufacturing and supply chains were slowed or stopped altogether in China. As orders for cars and smart phones piled up against the chips backlog, companies across sectors made the same calculation: diversify supply sources.

“During the pandemic recovery, foundries were full. Customers wanted more than we could supply so we looked to invest more in domestic production,” said Dan Malinaric, vice president of Microchip. “Shortages that existed in automotive and many other sectors meant our customers were hard-pressed to get what they needed.”

Meeting consumer demand was more than good business for Microchip. Microchip’s fabs are central to U.S. national security as they are the market share leader in supplying semiconductors to the aerospace and defense industry.

“Just as it’s good for government and our national security to have domestic production, it’s good for Microchip to own more of its own supply chain,” Malinaric said.

But to find public financing to help Microchip in Oregon was not so simple in 2021.

"Companies need to show they have state and local support to attract the federal investment,” said Monique Claiborne, president and CEO of Greater Portland Inc, the region-wide economic development organization. And compared to competing states, Oregon had little to show.

A 2021 Offer

In December 2021, aware of Microchip’s desire to build a new plant with a $5 billion capital investment and 600 new jobs, the state’s economic development agency, Business Oregon, extended the company a $2 million offer. The package included $1 million to create a workforce development program to upskill workers to meet Microchip’s hiring needs, $1.25 million from the Business Expansion Program (BEP) in a cash-based forgivable loan equal to the net revenue the state would receive in personal income tax from the company’s proposed new hiring, and below prime rate Microchip Industrial Development Revenue Bonds.

To qualify for the BEP loans, companies must have at least 150 employees and create at least 50 new jobs that pay over 150% of a county or state average wage (whichever is less).

“This would require additional conversations and planning, but could be a model moving forward supporting the high-tech industry in Oregon,” wrote Business Oregon director Sophorn Cheang. “We stand ready to support Microchip in a future request and support through the process.”

The 2021 conversation was hardly impressive.

“Oregon was lacking as we evaluated other states. Oregon didn’t have the same type of incentives that other states were bringing,” Malinaric said.

Mortensen, a leading developer and design-builder, has worked with Microchip and the workforce development community in Oregon and Southwest Washington since 2021 and saw what the chip maker was considering from other states. “Other markets have been more aggressive in attracting companies. Oregon has not been as aggressive,” said Mike Clifford, vice president and general manager of Mortensen, and chair of the GPI business development advisory committee.

Later in 2022, the state of New York, through its Green Chips Act, provided an estimated $275 million in additional incentives. The Empire State’s overall incentive package was $100 million greater than Oregon's. The major shortfall further inspired action from Claiborne at GPI after a Business Oregon Commission meeting revealed the state incentive funds were running low.

GPI Advocates for Oregon Business

Recognizing the critical link between local support and the pursuit of federal funding, Claiborne emphasized, “Acknowledging the reality is not enough; action is imperative.” Securing a project would be challenging without Oregon's financial support for businesses pursuing federal dollars, so Claiborne got proactive, doing television appearances, writing opinion articles, and escalating efforts to the state’s leadership.

One of those calls was to State Rep. Janelle Bynum, who later would chair the Oregon legislature’s joint semiconductor committee.

“It was Monique’s willingness to turn over every rock and look for help wherever she could,” Rep. Bynum said. “She was industrious without being off-putting, and it didn’t hurt to have Sen. Wyden nudging this along.”

On October 3, 2022, Claiborne emailed Mayor Stovall and Rep. Bynum in a message subject-lined “Project Semi Sweet.” “The company [Microchip] has indicated they are making a decision before the end of the year,” she wrote. “Gresham has pulled out all the stops. The State needs to beef up its incentive package. I urge you both to call Gov. Brown to request additional allocations to the Strategic Reserve Fund (SRF) and Oregon Business Expansion Program (BEP) for this project.” At the time, Oregon had about $11 million in cash incentives available for the ensuing eight months to attract and expand business in Oregon.

Business leaders called Claiborne’s efforts “instrumental” in the effort to evolve Oregon’s posture to be more business friendly. “GPI’s biggest play is connecting. Whether it’s companies already here looking to expand and grow or relocating here,” Malinaric said. “Without [Portland General Electric CEO] Maria Pope, Monique Claiborne, and Sen. Wyden, these things wouldn’t have happened in Oregon. They didn’t take no for an answer.”

Gresham having already secured local investments and tax exemptions for Microchip valued the acuteness GPI brought to the table. “The relationship between the private sector and government, it brings us all together to ensure these investments happen,” Gresham Mayor Travis Stovall said.

A State Evolves

As the global economy recovered from the impact of the pandemic lockdowns and semiconductor manufacturers worldwide diversified their production and supply chains, public financing of private industry – a tradition in Beijing – was getting a new look in Washington.

“It’s a competitive environment,” Malinaric said of the geopolitical competition for chips and fabs. “Government grants tend to help close that gap. The semiconductor task force started by Sen. Wyden and Gov. Brown was key in funding the requests Oregon needed to be competitive.”

Rep. Bynum lived Oregon’s evolution alongside Microchip for the last 20 years in the state.

She moved to Oregon from Michigan after the September 11th attacks with a business degree in hand and having accepted a buy out from an employer in the (sector).

“Nothing worked out,” she said. “It was sobering for a 26-year-old. I had the credentials, yet I couldn’t find a job.” Now with children of her own preparing to enter the workforce, Bynum says her work on economic development is focused on ensuring there are jobs in Oregon for their generation. “I want nothing more than for them to build their families and one day care for their aging parents in the communities they grew up in,” she said.

A lifelong Democrat, Bynum says she understands her party and Oregon government writ large needed to change its approach to economic development.

“Sometimes we’re just too hard to work with,” she said of the Oregon legislature. “This Microchip win showed we can still stand on our values, but we don’t have to be obnoxious about it. This is an excellent example of a solid public-private partnership with shared risks and rewards.”

“Our system is set up to be not as optimal,” she said, pointing to Oregon’s state bureaucracy siloes, in which the elected secretary of state oversees business registration, Business Oregon handles the governor’s economic development agenda of grants and tax incentives, and another elected official, the state treasurer, has its own investments and levers to incentivize business.

The momentum from the federal CHIPS Act and 2022 Intel announcement of a $20 billion investment in Ohio further spurred Oregon lawmakers to pursue more coordinated and effective paths to promote investments that attract and retain semiconductor players in Oregon.

Sen. Wyden and Gov. Kate Brown created the state’s first semiconductor task force to add focus to the state’s culture of collaboration. Its recommendations largely became the Oregon Chips Act. Rep. Bynum’s legislative committee, higher education institutions, workforce development boards and non-profit community organizations delivered. The state chips act allocated $190 million in grants to the sector plus $50 million in incentives.

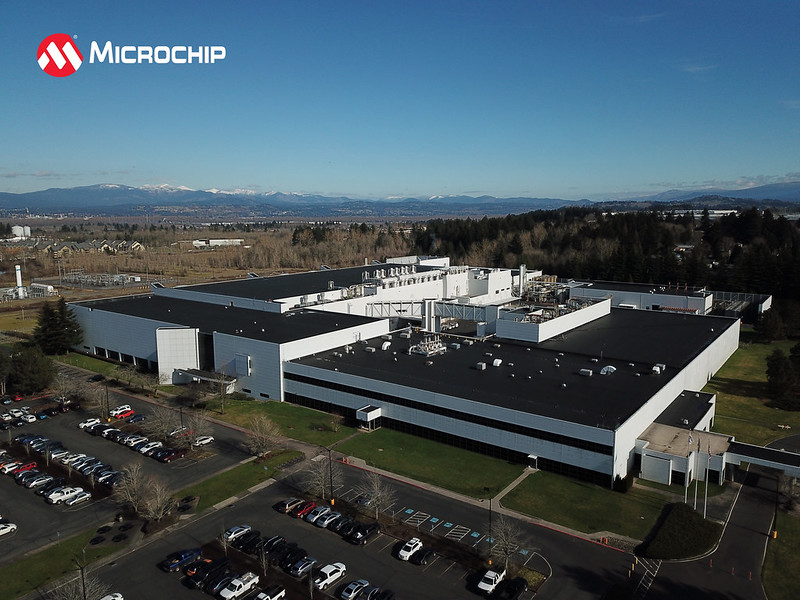

(photo courtesy of Microchip)

Oregon being the longstanding home of semiconductor research and development and the state’s renewed actions to secure that leadership position attracted attention from the Biden Administration. In April 2023, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo visited Oregon and delivered a message that may have just foreshadowed the federal money that would follow.

"The way you’re thinking about job training, investments in technology, investments in infrastructure,” Raimondo said at Portland Community College. “You’re doing everything right, and we just have to partner with you to help you be successful.”

It was music to the ears of companies like Microchip as they prepared applications for federal chips program funding and Oregon lawmakers, like Bynum, who had been advocating for the stronger public partnership to support the economic growth.

The tide had turned in Oregon and the country’s highest-level official on the issue was in town to be part of it.

“Having each tier of government supporting this business proposition was a major turning point in Oregon,” Bynum said.

Proof Positive

By the spring of 2023, Microchip announced it had added 300 new employees to its Gresham facility, with plans to hire as many as 300 more. The company has also already begun to expand and upgrade its 140-acre Gresham campus to increase manufacturing capacity. As part of the investment, Microchip is adding two cleanrooms and more than 160 new tools to its facility.

“The Oregon Chips Act in conjunction with the Federal CHIPS Act, the proof is in the pudding. We’re seeing investment in action,” said Clifford of Mortensen.

Eventually the state, through Business Oregon, the city of Gresham, and Multnomah County all came through to approve incentives of approximately $42.4 million for Microchip’s expansion of its existing operation.

“It’s a pretty impressive amount,” Malinaric said, “and these current Federal CHIPS Act announcements show the state continues to expand. “It’s an exciting time and it’s the first step toward many grants we hope we’ll see in Oregon.”

More Topics